Training - SPECIFICITY

“Specific” is an adjective that is widely used in relation to particular types of training in cycling. In the tradition of training theory, we talk about “specific workouts” usually when performing intervals in training that touch various zones or involve manipulation of cadence, often totaling a few dozen minutes of intensity.

But what does the word “specific” actually mean?

In my opinion, to define a workout specific in relation to a type of race, it is necessary for this training to largely replicate the physiological demands of the race.

If I were asked which session seems more specific for a 5-hour race, likely spending more than 1 hour in high-intensity zones, for example, comparing a long ride in zone 2 of 5 hours with a session of 20mins of vo2max work, I would probably respond that the first one is more specific, having at least the duration component.

In any case, I wouldn’t call either of them “specific work.”

It would be very convenient to know what threshold to surpass with the training stimulus to achieve supercompensation and subsequent improvement: the truth, in my opinion, is that we cannot know this, both because the physiology of each athlete is different and because depending on the day and training period, we have differences in internal load for a given workout that also modify the subsequent response.

As is often the case when we are at the mercy of chaos, many coaches try to theorize the perfect session based on parameters or mathematical models that aim for exact precision: is it really possible to achieve it, or given the unpredictability of the system, wanting to set very sharp and precise boundaries for a session or a concept risks leading us even further off track?

Returning to the concept of specificity, I like to think that the simplest way to train the body to do something is to repeat it as many times as possible.

While in the practice of technical gestures or skills this concept is well established, where the maximum number of well-executed repetitions is sought to learn a movement, with training it is often thought mainly about alternative ways to achieve something without focusing on what we want to achieve.

For example: in my career, I’ve seen many track sprinters do everything except run fast on the track, from gym workouts to countless different mobility and proprioception exercises, but from what I understand following the athletics world from a distance in recent years, top-level sprinters are now improving primarily by doing one thing: running fast, moving quickly, and recovering long enough to do it again.

If we talk about the tradition of cycling training, a strong contradiction emerges between two concepts emphasized by “old school” coaches: on one side, assigning “specific workouts” that have little to do with race demands (e.g., extremely low cadence, total work times often under half an hour), and on the other, claiming that it’s necessary to race frequently because no training can bring the improvements that racing brings.

Now, with the latter statement, I can partially agree, as racing is a technical skill as well as a physiological one, and certain psychological, practical, and tactical components can only be improved through repetition. However, I wonder if from a physiological standpoint it wouldn’t make more sense to prepare for races with true specific training, meaning that which replicates race demands as closely as possible.

In this way, we try to save ourselves from entropy and the mysteries of the adaptation process by doing exactly what we want to excel at, but in a more controlled context (no risks of crashes, much less mental stress, the possibility to rest and eat right after finishing, the option to take breaks in between).

I recall listening to podcasts by Olav Alexander Bu before the overwhelming victories of his two athletes who had just joined the Ironman circuit, where he talked about their typical training week. The weekend particularly consisted of replicating the Ironman distance at race intensity but divided over two days, or rather swimming + cycling and cycling + running, allowing for short breaks in between for measuring physiological parameters and “refocus”, effectively bringing home an Ironman every weekend throughout the preparation period.

In cycling, almost no one trains this way, and after my disappointing experience in Greece, I looked at the zone distribution of my long training sessions and realized that there was no way what I did last winter replicated what I would encounter in the race, unlike what I had done in other winters with more extreme training.

Out of fear of overdoing it, I convinced myself that training in a more controlled manner and with less fatigue might lead me to adapt better, but now I wonder if the improvements I had in the past with that approach didn’t mean that I had reached the ability to adapt to that significant workload and therefore, doing less at a lower intensity probably led me to de-training.

After Greece, I indeed switched to longer workouts, spending time in higher intensity zones, similar to race conditions, and it seems that results are already emerging.

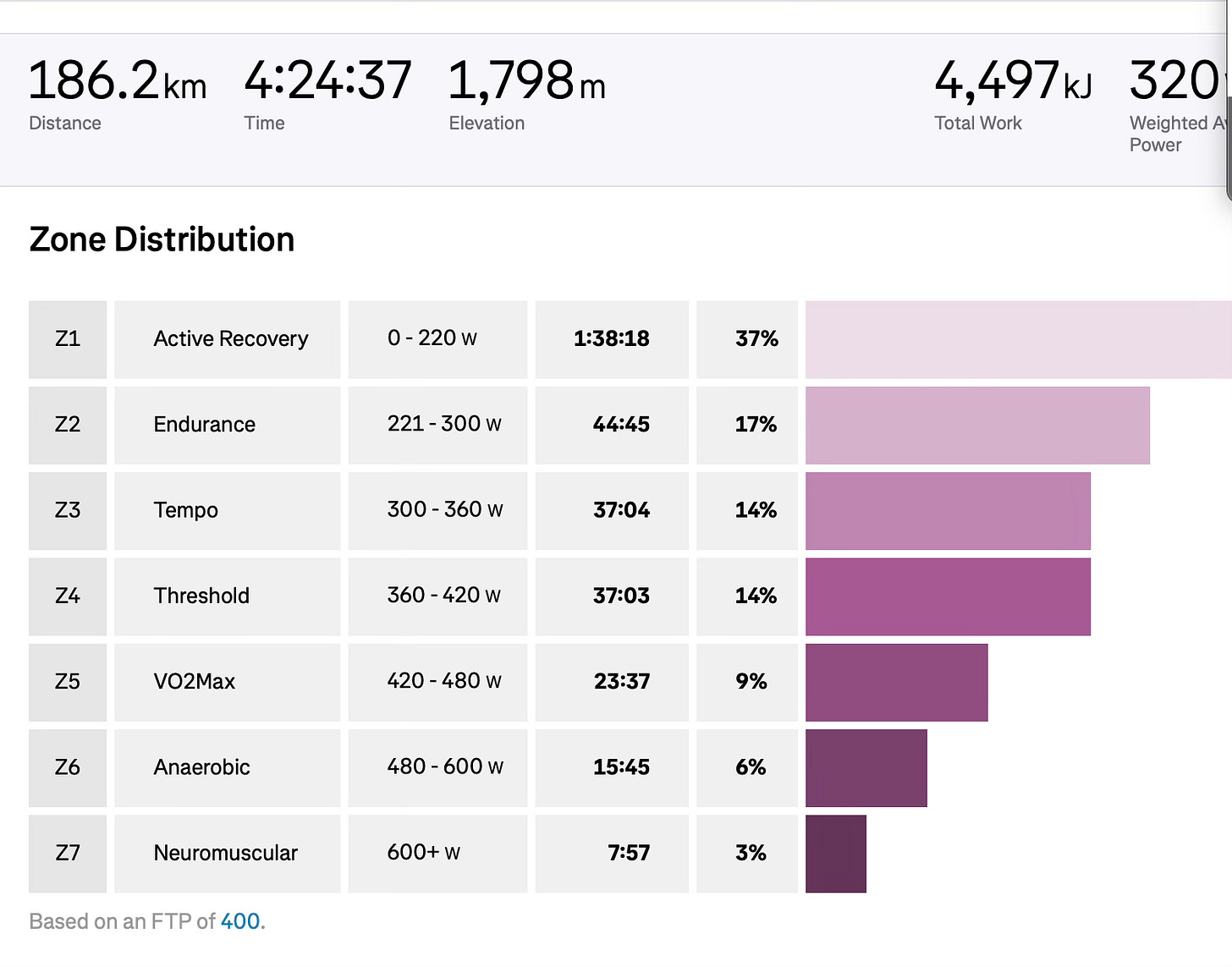

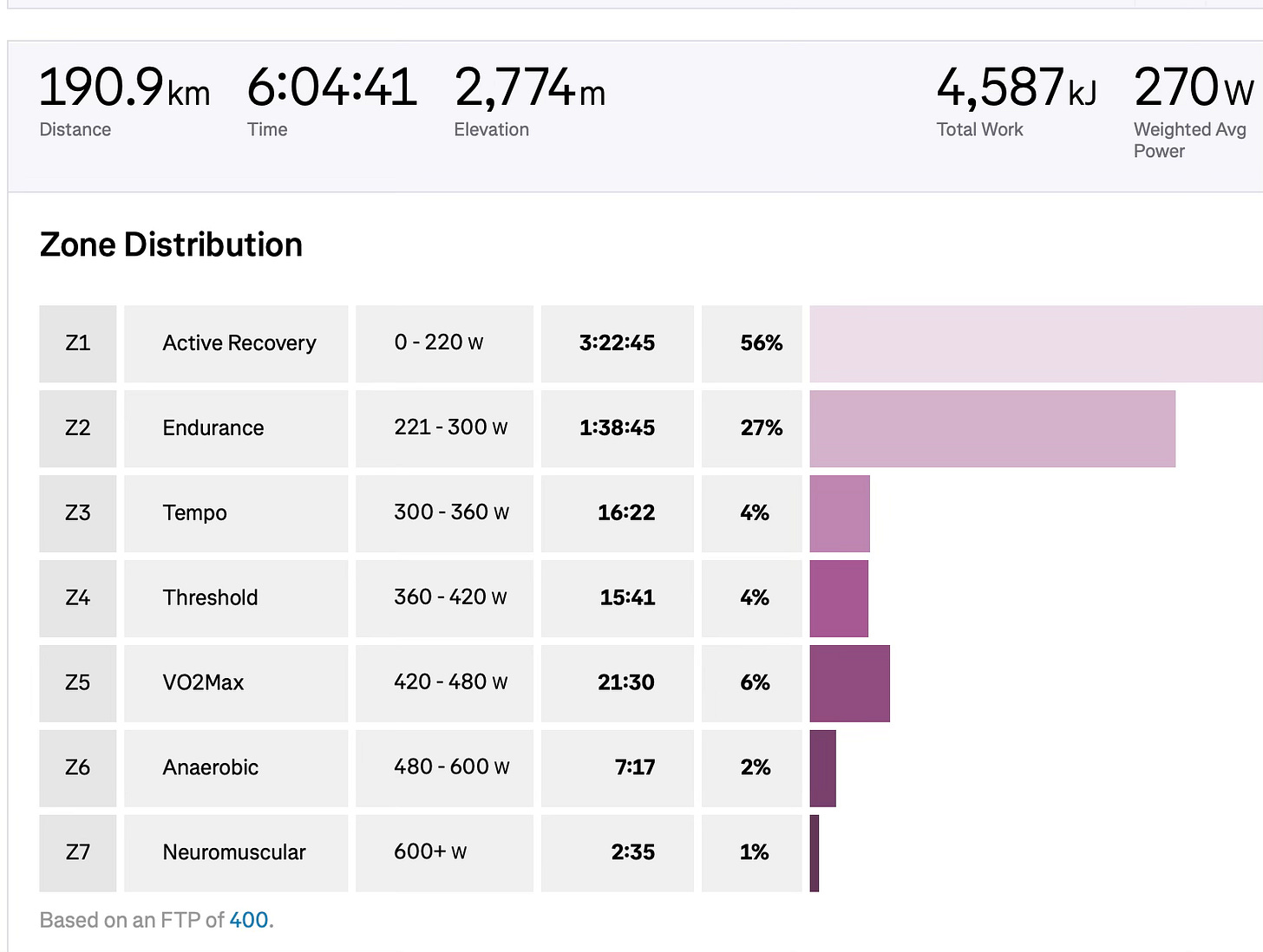

I’ll show you an example of the power zone distribution from the GP Rhodes and the race simulation training we did in Girona (one of the most intense workouts I did this winter):

GP Rhodes: 1h20 above threshold, 50min above 420w

Training: only 30min above 420w and 50min above threshold. Also, less z3 (contributes to glycogen depletion much than you’d expect.)

If I were preparing for hill climb races or aiming to improve my VO2 max, the distribution in zones from the second workout would be more than specific, fully covering the demands of what my event would entail.

However, if I am preparing for races with an intensity distribution like the one above, it’s evident that I am under-prepared.

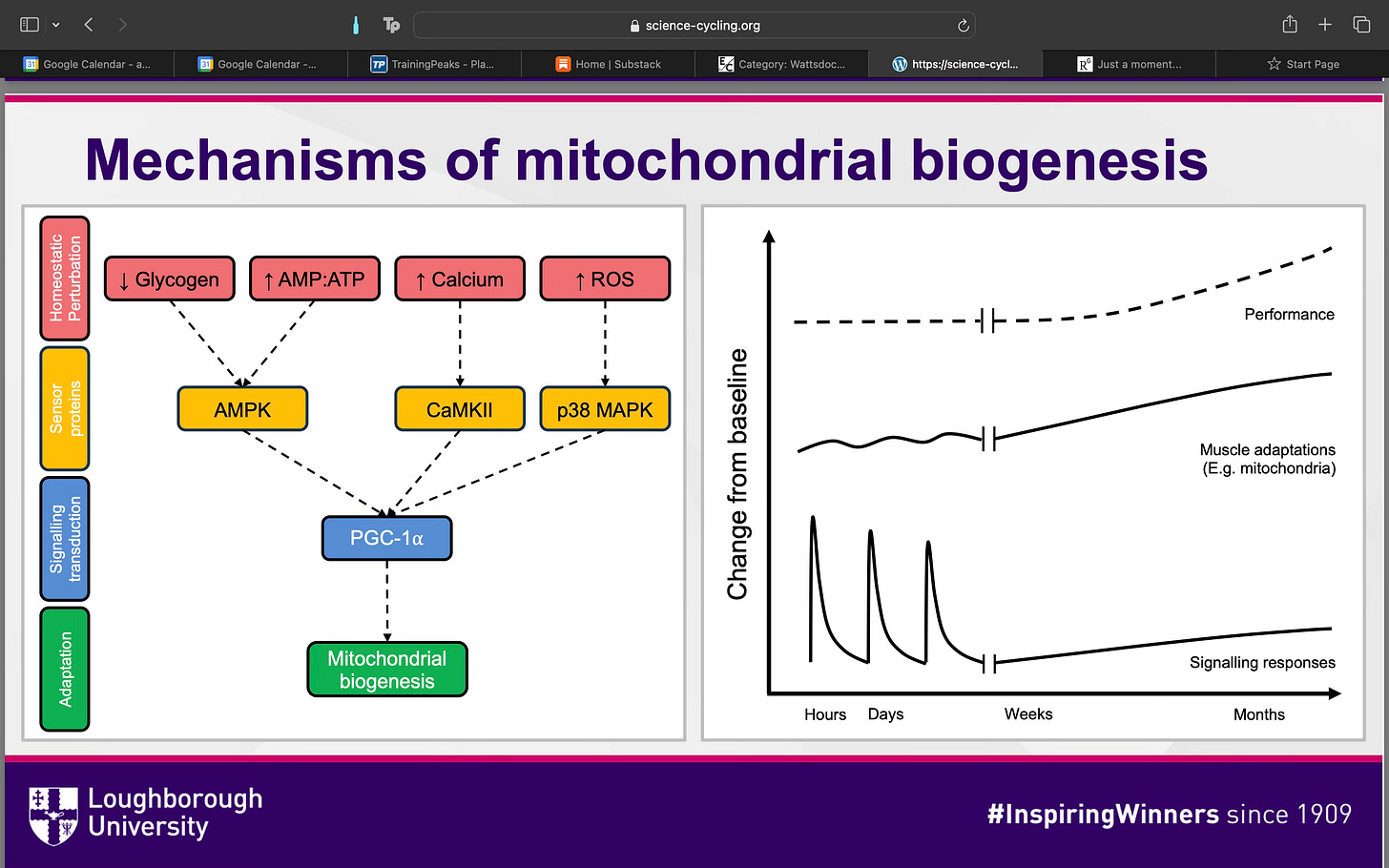

Certainly, there is a part of specificity that we can cover with the total work in kilojoules of the sessions, because if we look at the likely mechanisms that lead to adaptation, one of these is the calcium pathway, which can be replicated even without high intensities.

However, regarding the low glycogen pathway, we can hypothesize that this leads to a specific adaptation in the fibers where the level decreases. Therefore, only spending time in high zones can aerobically train that type of fibers, making them more durable—something we cannot achieve with high kilojoules spent in low zones.

Even anecdotally, we can certainly observe that many successful athletes adopt this approach of pushing themselves to the limit on certain training days, while allowing enough time for the body to recover on easier days. This is the case with David Roche in his current preparation for the Leadville 100, or for example, Mads Pedersen, who is famous for his 7-hour rides or more with a lot of intensity included, often riding behind a motorbike, etc.

In conclusion, I feel that if we aim to improve physiological parameters such as VO2 max or power over X minutes, we can try to train in a more classic way, as in most workouts, we reach a sufficiently high volume to exceed the demands in terms of kilojoules and total minutes above critical power (CP). At this level, we are likely already specific and can afford to experiment with different sessions to find which ones we enjoy most or which elicit the best response, which is what we've seen in literature in recent years (intermittent VO2 vs. continuous, etc.).

However, in the case of long races (the majority of cycling events), the physiological demands are so different from what is traditionally done that we cannot afford to follow only the guidelines from the literature.

I will try this approach on myself, as always, and I will seek to understand if replicating the exact demands of the race in a controlled manner is maybe the only way to manage the chaos of the human body in the training process.

Interesting piece.

Did you ever try to replicate a specific race effort for a goal race?

For example analyzing Strava segments for the goal race’s key moments and replicate that effort in a training session or even a block of those? It might not work as a general training plan but maybe it will for a specific event